By George J. Winter, Sr.

The Normandy landings, the fighting at St. Lô and Caen, Operations Goodwood and Cobra, and the subsequent Argentan-Falaise Pocket have always drawn major attention from historians, with respect to the early struggle for supremacy in France. This is as it should be considering their overall importance. Overshadowed by these major events are those countless small-unit actions that were just as violent and nerve-wracking to German and Allied participants. Yet the sum of these less noted engagements, now all but forgotten, were the underpinnings of the better-known military operations. One of these minor affairs, which involved an M4 Sherman/Mark V German Panther tank duel, occurred on August 4, 1944 just to the southeast of Saint-Sever-Calvados.

By the close of July 1944, the Cobra breakout was approaching full tide as the armored columns of U.S. First Army spread out across the base of the Contentin Peninsula. On August 3, Combat Command B (CCB) of the 2nd Armored Division, divided into two columns, had reached the vicinity of Sept-Freres and the village of Courson, farther to the west. The Combat Command had initially been separated into the two columns at the start of the offensive for the purpose of better control. Heading up the two segments were Colonel Paul A. Disney and Brig. Gen. Isaac D. White, who also commanded CCB. Although Disney’s command had, at the outset of the campaign, been designated the left column, the vagaries of battle and movement now placed it to the right of White’s unit.

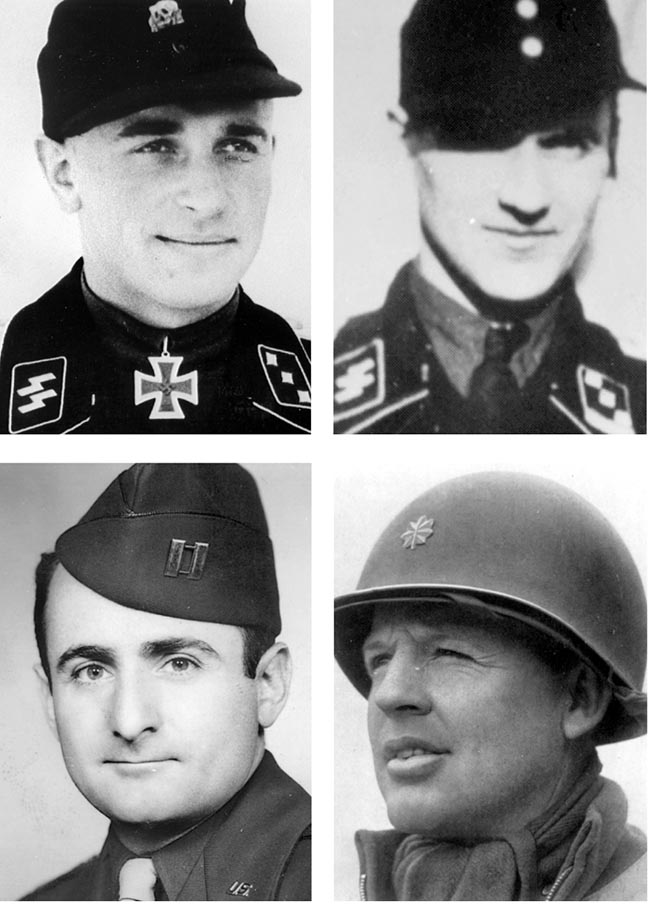

Both Disney and White were seasoned commanders. White, a graduate of Norwich University, had been associated with mechanized cavalry since the early 1930s. Appointed commander of the 67th Armored Regiment in June 1942, he would be succeeded by Disney after assuming command of CCB on April 5, 1943. Paul Disney, White’s junior, had a good combat record, which brought him the Silver and Bronze Stars with clusters, as well as the Purple Heart. He had received his colonelcy just before the landing of the 2nd Armored Division in Normandy, and now found himself at Courson.

The Courson column comprised the 2nd Battalion (the 67th Armored Regiment, Companies B, E, and F) and the 3rd Battalion (the 41st Armored Infantry Regiment), commanded by Lt. Col. Marshall Crawley. Artillery and engineers, as well as a platoon of the 702nd Tank Destroyer Battalion and a medical detachment, were in support. An adjunct to the column was Colonel Thomas A. Roberts, Jr., 2nd Armored Division’s Artillery commanding officer (CO). Roberts, a West Point graduate, class of 1920, was an innovative and aggressive artilleryman. An Illinoisan by birth, he would be awarded the Silver Star for action on July 29, 1944 as part of a military career that spanned more than half of his 44 years.

Saint-Sever-Calvados: German Panthers in the Waiting

Orders for the following day, Friday, August 4, called for Disney’s command to enter Courson, move southeast through Saint-Sever-Calvados and onto a major road leading to Vire, its ultimate objective being Champ-du-Bolt. With the start time 5:00 am, Disney’s command was led by Company F, 67th Armored Regiment and the 3rd Battalion 41st Armored Infantry. The remainder of his command was in close support, with the 110th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division, advancing on the right.

Passing through Courson the column continued toward Saint-Sever-Calvados. The unit reached the town at about 9:30 am and although it was subjected to enemy artillery fire, the command passed through it and continued slightly to the southeast. Here, it was entering a wooded area that was on the fringe of Foret de Saint-Sever, the forest of Saint-Sever.

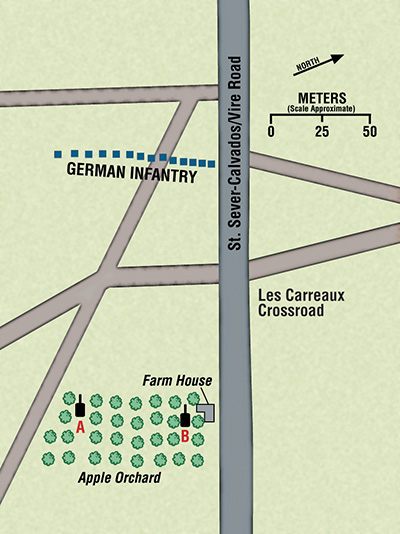

About a mile southeast of the town, and directly in the path of the American advance, stood two Mark V Panthers waiting in a fruit orchard to the left of the Saint-Sever-Calvados/ Vire Road. With good visibility of movement some 200 to 300 yards to their front, these monster tanks, weighing more than 44 tons, were heavily shielded, boasting 80mm (3.2 inches) of steel on the glacis or sloping face. The Panthers were armed with a 7.5cm gun as well as hull and turret machine guns. The Mark V was unquestionably one of the best tanks produced in World War II.

Positioned as they were, the German Panthers were covering a road complex that not only included the artery to Vire but also the Les Carreaux Road, which led into and crossed it from the north. Also to the German front was a narrow farm lane that branched off the Vire Road at a sharp angle and passed to the immediate left of the fruit orchard.

Within the grove one of the German panzers had taken up a position close to the Vire Road and a farm building on its right that bordered the thoroughfare. The second Panther stood some 50 yards to the left, both vehicles possessing a field of fire to their immediate front.

As a screen, a battered Vienna infantry battalion was dug in some 160 yards in front of the panzers. Its position, with reasonably good cover, lay within the apex formed by the Vire Road and the farm lane. Observing the partially fog-shrouded road and lane from his position in the panzer’s turret was SS Oberjunker (Senior Cadet) Fritz Langanke.

He had arrived at the crossroad early on the morning of August 4, having received direct orders from the commander of 2nd SS Panzer Regiment, commanded by Sturmbannfuhrer (Major) Rudolf Ensling, to set up a roadblock. Initially positioning his Panther on the right side of the Vire Road and under tree cover, Langanke helped post the infantry support after its arrival. Following the appearance of his company commander, Obersturmfuhrer (First Lieutenant) Joachim Schlomka, who had also been ordered to the roadblock, both panzers crossed the road and entered the fruit orchard. Langanke moved into the right corner of the grove near the road and Schlomka posted his panzer in the left angle close to the farm lane.

Having just turned 25, Fritz Langanke was a veteran of the campaigns in Poland, France, the Balkans, and Russia. A platoon leader in 2nd Company, 2nd SS Panzer Regiment—“Das Reich”—he was already credited with the destruction of 10 Allied tanks. Quick to react in a combat situation, he led his men in an action the month before, during the general German withdrawal, that won him the Knight’s Cross. Langanke’s skill, determination, and good fortune enabled him to bring the remains of his platoon and a ragtag collection of some six hundred infantry and their vehicles through the American lines.

Waiting along with Langanke in Panther No. 211 were the other members of his crew. Manning the cannon beneath the commander was the gunner, Rottenfuhrer (Corporal) Meindl from Sudetenland and Sturmmann (Private) Fahnrich, the loader, who came from Duisburg near the Rhine River. The radio operator, and also hull machine gunner, was Rottenfuhrer Pulm, whose home was in Dusseldorf. The most recent member of the group was the driver, Sturmmann Heil of Leipzig. Heil had joined the crew as a replacement for the previously wounded driver.

In the left corner of the orchard stood Joachim Schlomka’s Panther No. 201. Wounded five times during the war, Schlomka had joined the division in 1942. A quiet, imperturbable North German, he would be awarded the German Cross in Gold for action in Russia and at Percy, France. At Percy, just a few days previous, the 66th Armored Regiment of the 2nd Armored Division had suffered heavy losses, including an entire platoon of tanks of G Company. It was the stubborn defense of Schlomka, as well as two Panthers of his 2nd Platoon, that contributed to the denial of the town to the Americans for 24 hours. Two probes by Shermans failed, and the Americans were held up until the German evening withdrawal.

Although not mentioned in his German Cross in Gold citation, Schlomka oversaw the removal of American wounded from their disabled tanks, as well as the search for them for shelter in French homes and for medical assistance. Further, he ordered that the wounded “stay in the French houses” until they were returned to their units.

With the morning passing, the fog still limited visibility of movement where the main road was joined by the farm lane, but it did not hinder the advance elements of Disney’s column. As Langanke watched, an American tank came in sight. He could see the American commander looking out of the turret as the vehicle slowly approached. In Langanke’s panzer, the motor was shut down, requiring the crew to move the turret by hand. This they did and fired a round. The projectile missed, and the American tank passed behind the farm structure.

While Schlomka maintained his position, the driver of Langanke’s Panther started the motor, backed up, and rushed to the road, which was somewhat elevated above the orchard. Gaining the road with the turret already turned to the right, Langanke gave the requisite orders to fire at the American tank that had continued down the road. The round destroyed the motor of the Sherman at a distance of some 50 yards. Langanke could see the American commander leap from the tank.

Anticipating more Shermans approaching along the road, Langanke ordered the panzer to swing left. As expected, he now faced two more American tanks at a distance of some 150 yards, one on each side of the Vire Road. In response to Langanke’s commands, the gunner fired. Langanke recalled, “We knocked them out with just one round each.”

Almost immediately after this success, while still on the road, the German looked to his left front and saw infantry running with their hands up. He mistakenly assumed they were surrendering Americans. In fact, these were German infantry who had capitulated. Without being aware of it, the panzer crews had been stripped of a good portion of their infantry support, an absolute necessity for the close combat in which they were engaged.

Sometime around noon, after Langanke’s panzer had returned to the orchard, his regimental commander, Rudolf Ensling, appeared. As part of his inspection of the roadblocks established by the regiment, Ensling stayed long enough to examine the immediate posting. Pleased with the action taken by the panzer crew, he left.

Both Panthers now settled down and awaited the Americans’ next move. As the German commanders gazed from the turrets their view was limited on the right and left by both bushes and trees, and Schlomka was particularly troubled by the presence of a hill to the front. It rose well above the level of the road and was approximately 900 to 1,000 yards away. In his opinion the high ground provided a clear view for artillery observation and the fire that could be brought down on their position. In fact, Schlomka’s fears were about to come to pass.

“To Stop the Enemy Or To Die”

As for Langanke, the relentless and overwhelming pressure of the American advance during the previous two weeks had left him with few illusions about his future. The desperate conditions of the forced German withdrawal had created a back-to-the-wall atmosphere that surely made him a more tenacious opponent. He would later recall: “It was a hopeless situation, trying by all means to stem the tide, regardless of how dangerous it was and how slim the chances were to survive.… There were only two possibilities: to stop the enemy or to die.”

The Americans, now stalled on the road, decided to hold what ground they had while flanking the German position with troopers of the 41st Armored Infantry Regiment. As part of this dislodgment effort, artillery fire would first blanket the area. To this end the hill that concerned Schlomka was indeed being used as an observation point in order to get a fix on the enemy’s location.

Among the viewers who had climbed to the crest of the elevation was the commander of E Company, Captain James R. McCartney of West Virginia. With his Shermans idle on the road and wanting an idea of what was to his front, McCartney, Pennsylvania born and a graduate of West Virginia University, said later, “Nothing got our attention like an 88 or a Panther.” Atop the rise he saw Colonel Roberts, the division’s artillery commanding officer. McCartney remembered him as an “impetuous man.” He heard the colonel say, “We have to get through that roadblock.” Presently, Roberts left the hill and McCartney followed, but not without having scanned the area with his binoculars. “I could not see the enemy but it wasn’t a great spot for the Germans,” he remembered years later.

Sometime before McCartney climbed to the high ground, Captain Louis H. Tankin, a Marylander and graduate of Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins University, had been called by radio to the rescue of three wounded German soldiers. In charge of the column’s medical detachment, Tankin headed for the front.

Traveling by jeep, Tankin would later remember, “We continued to follow the call up into a hilly area which was heavily forested. I heard small arms fire and then came to the edge of a clearing in the woods,” which bordered on a large ammunition dump.

Alighting from the halted jeep while his driver and aid man remained behind, Tankin later reported, “I got out and walked up to a lieutenant from 28 Division. He pointed to three German soldiers. They were pretty badly shot up.” Within moments of Tankin’s arrival enemy shelling forced the lieutenant to order the withdrawal of his endangered men from the vicinity of the dump. This left the medical officer alone with the wounded enemy. “I called to my aid man and told him to throw me a grappling hook.… I attached it to the wounded men. They were dragged out one by one.”

After the Germans were moved to the rear by ambulance, Tankin returned to the column where he received a message to report to the commanding officer of 2nd Battalion—67th Armored Regiment. That CO was Lt. Col. J. Davis Wynne, a 35-year-old Arizonan. When Tankin found Wynne he was standing near his command half-track, which was part of the stalled column on the road. The doctor remembered Wynne saying, “We have three tanks hit up ahead. I want you to go in and get them out.” Warned that he had only 15 minutes before the area would be shelled, the medical officer wondered whether he, his driver, and medic would ever return. These last two were Private Stanley R. Yarmuth, the medic; and Private Russillo, the driver, whom Tankin described as a tough, young Italian-American. As their jeep made its way down the road they passed American tanks and armored vehicles strung out one behind the other. After receiving directions, they continued and neared the knocked-out Shermans.

Before Tankin’s arrival on the scene, Schlomka, who had joined Langanke at Langanke’s panzer, watched as a jeep bearing a red cross drove up to the disabled American tanks. There, the occupants ministered to the tank crews. Through his binoculars Schlomka saw another jeep (this one Tankin’s) drive up, halt at the tanks, and then continue toward the German position.

Although Schlomka had no doubt about the function of the vehicle’s passengers, he was puzzled by the need for their approach. He had noticed no destroyed armor or wounded Americans during his drive up to support Langanke and thus behind their position to which the American jeep might want to venture. Concerned that the Americans in the jeep would observe and report his position as well as the size of his force if they were allowed to return, “we attempted to give them a sign of refusal but they did not stop until they reached the panzer of Langanke.”

Tankin’s memoirs do not reveal why he drove to the German position. Possibly he was looking for more casualties to treat, German or American.

In any event, Schlomka ordered Tankin and his men to remain in the jeep. Just then the American artillery opened up. The German recalled, “I could not let the jeep and medical people stand on the road under the fire of their own artillery.” To resolve his problem, before returning to his panzer in the orchard, Schlomka ordered a nearby infantryman to accompany the Americans to the rear in the jeep, with instructions that they not use their radio but that they could give assistance to any of their wounded they encountered along the way.

The artillery barrage that now enveloped the area was heavy and appeared to the Germans to be concentrated on the orchard. Pinned down as they were, with shell fragments striking the hulls of the panzers, the crews were under a great deal of stress. They were also hungry, thirsty, and at a point of almost complete exhaustion, brought on by little chance to rest or sleep over the past week. Thus in spite of the situation they were in, members of the crew began falling asleep. Langanke, in fact, changed places with his gunner, Meindl, allowing him to lean his head against the sighting scope and get a bit of sleep.

It didn’t last long. Soon enough Langanke climbed back to his accustomed turret position and checked his front. He recalled: “A Sherman appeared on the road, swerved into the lane in front of us and came rushing toward our orchard at full speed, its gun pointing straight at us.” The suddenness of the American appearance was a surprise to the Germans, because it contradicted what they considered the usual pattern of an American advance—resistance countered by lengthy shelling, air attack, capped by an armored assault.

Schlomka also saw the advancing Sherman and kicked his sleeping gunner. The man fired, believing the gun was at a setting for armor -piercing rounds. The shell passed over the American, as did the second and third rounds. The German tankers later discovered that the gun had been left at a previous setting, which was for high-explosive shells.

A Nerve-Wracking Game Of Chicken

Langanke, observing the misses, realized, “Now it was a race against death between the Sherman crew and ourselves. Their gun pointed straight at us but they had to correct the elevation. We had the right elevation but were desperately traversing (by hand) to get the final lay. I had my head out of the cupola and got the impression my eyes were exactly in line with the Sherman’s gun barrel when we were ready to fire. Our first round destroyed the tank. The daredevil, straight on drive, within a hair’s breadth of success, came to an end some 50 yards in front of us. The commander was lucky enough to bail out and get away, as far as I could see. This was the most daring and exceptional single action of any American soldier I witnessed during the war.”

Once again the shelling, along with air strikes, picked up. With the hatches closed for safety, now heat built up, further fraying the crews’ nerves. The shelling blasted away the radio antenna of Langanke’s vehicle and destroyed the cupola scope, blinding the commander to enemy movement. Even so, Langanke once again nodded off, a sure sign that the limits of endurance were near.

Finally the shelling ceased and shortly machine-gun fire began to hit Langanke’s panzer, which was an indication that enemy infantry were not far distant. Schlomka, in the adjoining Panther, spotted infantry moving in from the left. “I knew that they would encircle us in a short time. I gave my driver the order to first drive backwards to the road and then to the right. After moving approximately 100 yards, I stopped to give covering fire to Fritz.”

Langanke was now fully aroused from his torpor by a combination of machine-gun fire, the sound of Schlomka’s tank starting up, and the slamming of an uprooted tree against his Panther. Assuming that his company commander was moving to engage Shermans on the road, Langanke ordered the driver Heil to follow, while he took the risk of opening the turret hatch to peer over the rim. Moving at high speed the Panther reached the roadway and swung around, taking a burst of hits as it did so. Although Heil and Meindl were unable to discern anything through their apertures owing to damage from the strikes, Langanke could make out a number of Shermans lined up on the left of the road in back of one of the previously destroyed tanks. He recalled that they were positioned one behind the other, “so that only the gun of each tank could shoot along the turret of the vehicle in front, and they were firing salvoes.”

Langanke reacted quickly in order to place the knocked-out American tank between himself and the Shermans. This maneuver would force each enemy tank to circle around the disabled Sherman and come into view individually, giving the Panther a one-on-one opportunity to fire. Explaining his plan to the crew, Langanke, through the intercom, ordered Heil to pull to the left. While in the act of turning, the Panther was hit “by a salvo mainly on the sloped glacis” so hard “that the welding seam between the front and side plate of the hull sprang open.”

“Bail Out!”

The shock of the blows also destroyed the intercom radio, cutting off normal communication with the crew. With Fahnrich, the loader, feeding shells into the breech, Meindl reacted to Langanke’s hand tapping on his shoulders (left/right) for firing. Unfortunately, with the din, Heil was unable to hear the commander’s shouted change of direction to “straight on” and continued to turn left, placing the panzer in a broadside position across the road.

From his post farther down the road, Schlomka, standing in his open hatch, could see that Langanke had turned “with the right flank of his panzer facing towards the house, which was located nearby along the road.” Schlomka could also see that American infantry had occupied the farm building and that bazookas were threatening his comrade’s panzer. Schlomka ordered armor-piercing shells to be fired at the structure. But just then Schlomka saw an explosion rock Langanke’s panzer, which had been hit by a bazooka from the right side of the road.

Inside his panzer, Langanke caught a glimpse of his loader standing “in a big flare. It was as if a great number of sparklers were burning. I only hollered, ‘Bail out!’ and jumped out of the cupola into the road ditch.” Although the gunner and wounded loader followed their commander, Heil and Pulm were caught inside the burning panzer by automatic weapons fire. Desperate to escape, Heil pulled the Panther close to the side of the road. Then he and Pulm opened their hatches and jumped out into the safety of the ditch.

While Langanke and his crew were escaping the doomed Panther, Schlomka with his 7.5cm gun silenced the fire coming from the farm building and drove the American infantry on the left to cover with his turret and hull machine guns. Reaching Schlomka’s Panther, the dismounted German crew watched as one explosion after the other shook their burning panzer.

The crew of the destroyed Panther then made its way back to the command post of its regiment, a distance of about a half-mile. Meanwhile, Schlomka’s Panther withdrew slowly, using the sloping contour of the road as a cover from enemy fire.

Now late in the afternoon, Colonel Disney’s column secured and “consolidated their position for the night.” The 2nd Battalion of Lt. Col. Wynne withdrew after being relieved by tank destroyers. The roadblock fight was over, but like so many other minor actions, it was short, vicious, and not without cost.

The Germans lost more than a hundred infantry, most taken prisoner, one Panther tank destroyed, and a crewman wounded. They held up the Americans all day.

The Americans lost five tanks, 15 killed or wounded, and three of the medical detachments taken prisoner out of the armored column. Another 30 casualties marked the efforts of the armored infantry flanking the tanks in the orchard. But then they continued their inexorable advance deeper and deeper into the heart of France.

Afterword

Captain James R. McCartney, CO—E Company, 67th Armored Regiment, survived the war. He remained with his command until posted to a staff position just before the Battle of the Bulge. He was the last of the original company tank commanders who landed in France on June 14, 1944.

Captain Louis H. Tankin, CO—Medical Detachment, 48th Armored Medical Battalion, survived the war. Transported to Germany, he was confined in a Prisoner of War camp until the area was overrun by the Russians. Although freed, his experiences were harrowing as he made his way by foot, truck, and train to Odessa and finally, home.

Colonel Thomas A. Roberts, CO—2nd Armored Division Artillery, was killed shortly after leaving the artillery observation post atop the hill. He and all the members of his forward observation tank died when the vehicle was struck by antitank fire.

Obersturmfuhrer Joachim Schlomka, CO—2nd Company, 2nd SS Panzer Regiment, survived the war. Promoted to Captain, he was appointed regimental adjutant before the Ardennes Offensive. After the surrender he spent 10 years as a Soviet Prisoner of War.

Oberjunker Langanke survived the war “pursued by luck.” Rising to the rank of Obersturmfuhrer he became commander of 2nd Company, 2nd SS Panzer Regiment. After hostilities ended he was imprisoned by the Americans for two years and spent a third as “a guest of His Majesty.”

Rottenfuhrer Meindl and Sturmmann Fahnrich, within weeks, were trapped against the Seine River at Elbeuf by elements of the 66th Armored Regiment. Attempting to escape by swimming across the river, they drowned. Rottenfuhrer Pulm rose to the command of a Panther. He was killed by a Russian shell fragment near Saint Polten, Austria, in the last days of the war.

Sturmmann Heil survived the war.