Two thousand years ago, the proudest boast was civis romanus sum. Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is “Ich bin ein Berliner!”.

The speech is considered one of Kennedy’s best, both a notable moment of the Cold War and a high point of the New Frontier. It was a great morale boost for West Berliners, who lived in an enclave deep inside East Germany and feared a possible East German occupation.

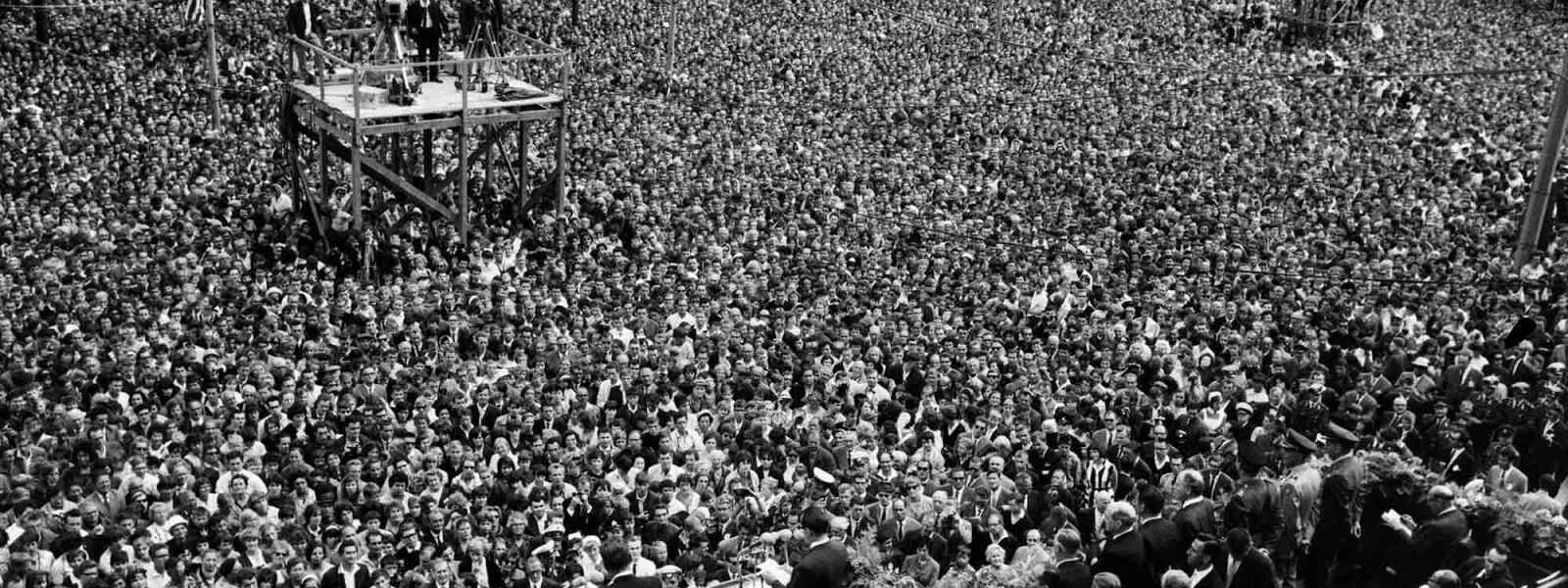

Speaking from a platform erected on the steps of Rathaus Schöneberg for an audience of 450,000, Kennedy said: Two thousand years ago, the proudest boast was civis romanus sum [“I am a Roman citizen”].

Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is “Ich bin ein Berliner!“… All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words “Ich bin ein Berliner!”.

Kennedy used the phrase twice in his speech, including at the end, pronouncing the sentence with his Boston accent and reading from his note “ish bin ein Bearleener”, which he had written out using English spelling habits to indicate an approximation of the German pronunciation.

Another phrase in the speech was also spoken in German, “Lass’ sie nach Berlin kommen” (“Let them come to Berlin”), addressed at those who claimed “we can work with the Communists”.

Kennedy surveys the Berlin Wall from a special viewing platform.

President John F Kennedy giving a speech at the Schoeneberg city hall in Berlin, where he said his famous German sentence “Ich bin ein Berliner” (I am a Berliner) to underline the support of the United States for West Germany and his empathy for people living in the divided city of Berlin.

While the immediate response from the West German population was positive, the Soviet authorities were less pleased with the combative Lass sie nach Berlin kommen.

Only two weeks before, Kennedy had spoken in a more conciliatory tone, speaking of “improving relations with the Soviet Union”: in response to Kennedy’s Berlin speech, Nikita Khrushchev, days later, remarked that “one would think that the speeches were made by two different Presidents”.

There is a misconception that Kennedy made a risible error by saying Ich bin ein Berliner. By using the indefinite article “ein,” he supposedly changed the meaning of the sentence from “I am a citizen of Berlin” to “I am a Berliner” (a Berliner being a type of German pastry, similar to a jelly doughnut).

The indefinite article is omitted in German when speaking of an individual’s profession or residence but is still used when speaking in a figurative sense.

Since the President was not literally from Berlin but declaring his solidarity with its citizens, “Ich bin ein Berliner” was the only way to express what he wanted to say.

A further part of the misconception is that the audience of his speech laughed at his supposed error. They instead cheered and applauded both times the phrase was used.

They laughed and cheered a few seconds after the first use of the phrase, only when the president made an intentional joke. Poking fun at his own pronunciation of the phrase, he said, “I appreciate my interpreter translating my German!”.