Unless the chancellor’s capital spending increases stimulate private investment, expect more tax rises ahead

Choosing to hold a bumper tax-raising budget the day before Halloween was always going to create presentational problems for Rachel Reeves. If you announce plans to borrow more and increase the size of the state you can expect the headline writers to have fun at your expense. The Daily Telegraph’s “Nightmare on Downing Street” summed up the mood.

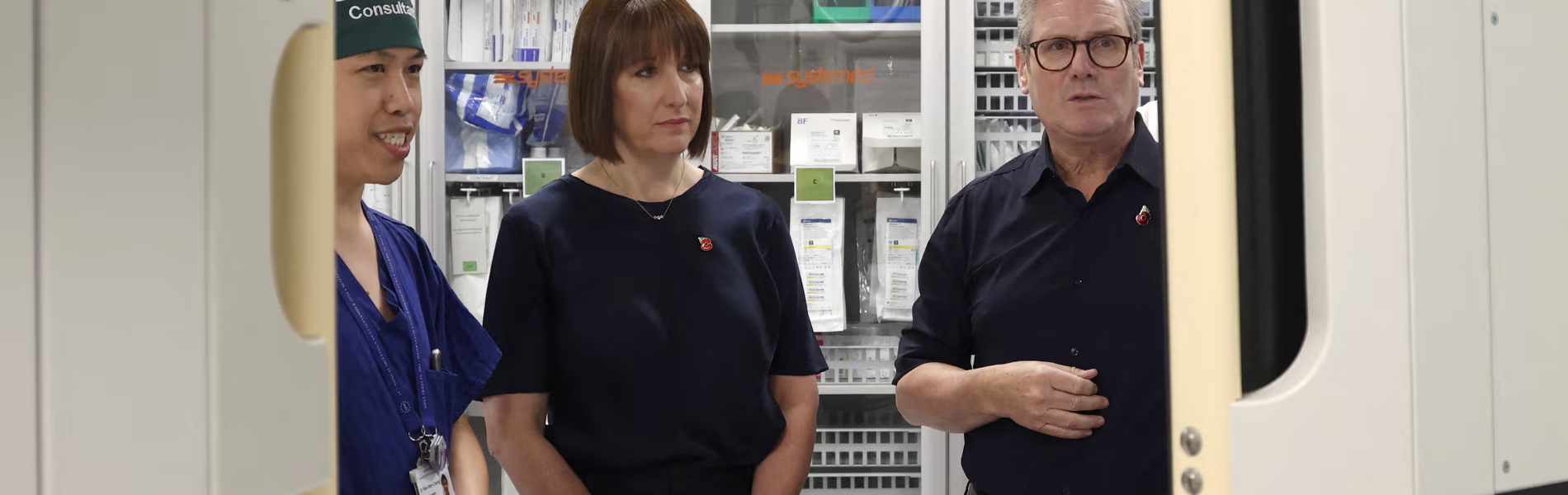

Reeves is not naive and knew what was coming. But while the chancellor would have preferred more positive headlines, a budget is judged not on its day one reception but over months and years.

Here there was better news for Reeves. She received some heavyweight support for her decision to increase public investment from the International Monetary Fund and the Institute for Fiscal Studies. Both said higher spending on infrastructure was the right thing to do, even if it would take time for the benefits to feed through into stronger growth.

The Office for Budget Responsibility says that by the end of the decade, higher capital spending will increase the supply potential of the economy by just 0.14%, rising to 0.43% in a decade’s time. But this is just one estimate, and assumes higher public investment will lead to higher interest rates, which in turn will dampen private investment.

But, as the IPPR thinktank has noted, the recent experience of the US suggests a more positive outcome. There, the expansionary fiscal policy and the activist industrial strategy has had the knock-on effect of stimulating private investment. The IPPR thinks the boost to the supply capacity of Reeves’s capital spending increases could be three times as great as the OBR is forecasting.

It was not all good post-budget news for the chancellor. Despite preparing the ground for higher taxes and spending, there has been a rise in the cost of servicing UK government debt of just over 0.2 percentage points. This needs to be put into perspective: compared with the market reaction to Liz Truss’s mini-budget it was a tremor rather than an earthquake, but worrying all the same.

The IFS also mingled praise with a caution that the big increases in real day to day spending covered only this year and next – with the planned rises for future years not sufficient to prevent real-terms cuts in some Whitehall departments. Spending goes up by 4.3% this year, 2.6% next year and by 1.3% thereafter.

The thinktank is not quibbling with the upfront increases, which it sees as justified given the “unrealistic” plans inherited from Jeremy Hunt. Where it takes issue is with the idea that spending growth will fall to 1.3% a year thereafter, because given the expected increases for health, defence and education, this would mean real cuts for other departments.

It assumes spending will increase by more than 1.3% a year from 2026-7 onwards, and under Reeves’s fiscal rules there is not much scope to borrow more to pay for it. It will help if the economy grows more quickly than the OBR predicts. If it does not, taxes will again need to rise.