Rheinwiesenlager: The Notorious American Prison Camps That Held German POWs Following WWII

There were hundreds of thousands of prisoners of war (POWs) taken during World War II. Under the Geneva Convention, it was required they receive certain standards of care, yet those held at camps operated in Allied-occupied Germany were purposefully classified in a different way, so that these requirements could be negated. Known as the Rheinwiesenlager – officially Prisoner of War Temporary Enclosures (PWTE) – they’re seldom spoken about.

Allied success in Europe following the D-Day landings

Following the incredible success of the D-Day landings, the Allies swept through occupied countries and into Germany. While some enemy soldiers continued to fight, many surrendered, leaving the Allied forces responsible for their care.

Initially, the prisoners were split among the British and Americans, but this changed in early 1945, when the former refused to accept any more individuals into their existing camps. Instead, the burden fell upon the Americans – a monumental task, given the number of German POWs was steadily increasing the further the Allies pushed into the country.

The solution created by the US Army was the Rheinwiesenlager, a series of prison camps established throughout Allied-occupied Germany. While they initially opened in April 1945, they became even more important after Germany’s surrender the following month, as the camps became a means of preventing a potential revolt against the Allies.

Layout of the Rheinwiesenlager

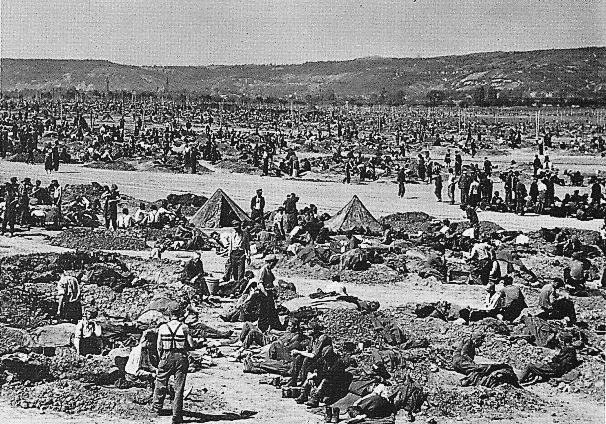

The Rheinwiesenlager were built on Allied-controlled land in West Germany. They were developed on farmland near railways by enclosing the designated space with barbed wire. The plots of land were then divided into smaller camps, which held anywhere from 5,000-10,000 people each – at least, that was their intended occupancy. Many of the camps saw occupancy levels surpass 100,000 prisoners, with estimates placing the overall total between one and 1.9 million.

Those held at the Rheinwiesenlager were generally unexceptional members of the Wehrmacht, while German officers, members of the SS and others interest were taken elsewhere.

Much of the internal organization of the camps was passed to the prisoners themselves, forcing them to manage their own work, medical care and cooking. Oftentimes, the guards who watched over the enclosures were themselves prisoners, bribed with more resources than their peers, so they’d ensure others remained within the barbed wire fences.

Within the compounds were buildings used predominantly as kitchens, medical facilities and for administrative purposes. What they weren’t used for was housing the prisoners. Instead of having accommodations, most were forced to dig holes in the ground.

Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs)

If sleeping in outdoor holes wasn’t indication enough, these prisoners were treated very poorly by their captors. Much of this was facilitated by their categorization – not as POWs, but as Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs).

Before the Rheinwiesenlager opened, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower established the new classification, as it meant DEFs wouldn’t have the same rights granted to POWs under the Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War (1929), as they were members of state that no longer existed. This allowed many things to happen.

It meant the Americans could “legally” prevent the Red Cross from visiting and stop the organization from sending supplies. The Geneva Convention was designed to prevent the poor treatment of POWs. Without such protections, the DEFs were mistreated with little to no consequences suffered by their captors.

All this has led many to now view the inhumane actions of Eisenhower and those operating the Rheinwiesenlager as purposeful.

Rheinwiesenlager conditions

Overall, the conditions in the Rheinwiesenlager were horrific.

Historian Stephen Ambrose investigated many claims made about the camps, and concluded, “Men were beaten, denied water, forced to live in open camps without shelter, given inadequate food rations and inadequate medical care. Their mail was withheld. In some cases prisoners made a ‘soup’ of water and grass in order to deal with their hunger.”

Begging for more food wasn’t an option either, as those prisoners were often shot as “escapees,” should they have gotten near the barbed wire fences. Reports also claim locals would be shot if they tried to provide aid to the POWs.

Legacy of the Rheinwiesenlager

Given the living conditions of the Disarmed Enemy Forces, it’s no wonder the death toll was high. However, because they weren’t officially known as prisoners of war, few records were kept. Instead, many Germans would simply go missing from roll call, never to be seen again.

Due to the lack of records, death estimates vary, depending on who you ask. The official statistics from the US Army state that around 3,000 people died while in the Rheinwiesenlager. German estimates, however, provide a figure of 4,537.

James Bacque, the author of Other Losses: An Investigation Into the Mass Deaths of German Prisoners at the Hands of the French and Americans After World War II, alleges the number is between 100,000 and one million. However, his claims have been discredited by his peers.